Nigeria has reversed a three-year-old policy that required early-grade teaching in indigenous languages, reinstating English as the medium of instruction from pre-primary through university.

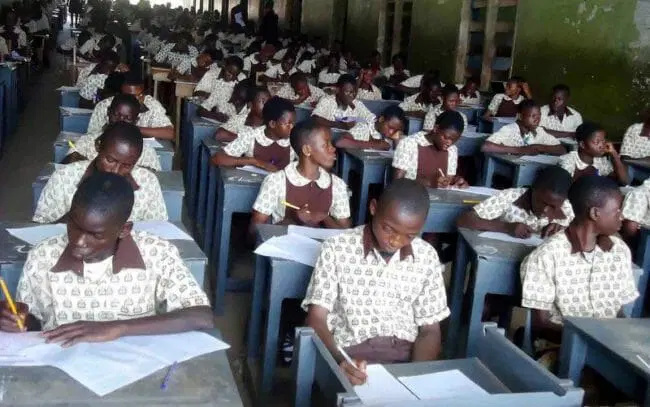

Education Minister Tunji Alausa said the programme, introduced under former minister Adamu Adamu, failed to improve outcomes where it was most widely adopted. Citing results from WAEC, NECO and JAMB, Alausa said “mass failure” in some zones correlated with aggressive rollout of the mother-tongue approach.

Supporters of the U-turn argue that Nigeria lacks trained teachers and learning materials across dozens of local languages and that national exams are set in English. “Do we have trained teachers to teach in the dozens of indigenous languages? The answer is no,” education expert Aliyu Tilde told the BBC, adding that better-qualified teachers are the more urgent need.

Some parents also welcomed the move, saying early exposure to English would help children in a globalised economy. Others counter that the policy was dropped too quickly. Social affairs analyst Habu Dauda said three years was “too little to judge” a major shift that requires long-term investment in teacher training and textbooks.

The decision revives a longstanding debate in Nigeria: how to promote the country’s linguistic diversity while meeting the practical demands of a unified curriculum and an English-dominant testing and admissions system.