A push by African governments to court high-end visitors is delivering scant benefits to nearby communities and can do more harm than good, according to University of Manchester research published Tuesday in African Studies Review.

The study says the “high-value, low-impact” pitch often breaks down on the ground. All-inclusive resorts are typically walled off from local life, employ relatively few locals, and discourage off-site spending by bundling food, entertainment and transport in-house. Many of the most profitable eco-lodges are foreign-owned, with a large share of tourist dollars leaking abroad via overseas tour operators, imported food and repatriated profits, it adds.

Researchers argue the model deepens inequality: gains pool with foreign operators or a small domestic elite while most tourism jobs remain low-paid. Rising air capacity and corporate interest have boosted arrivals, but the paper cautions that momentum does not automatically translate into broad-based development.

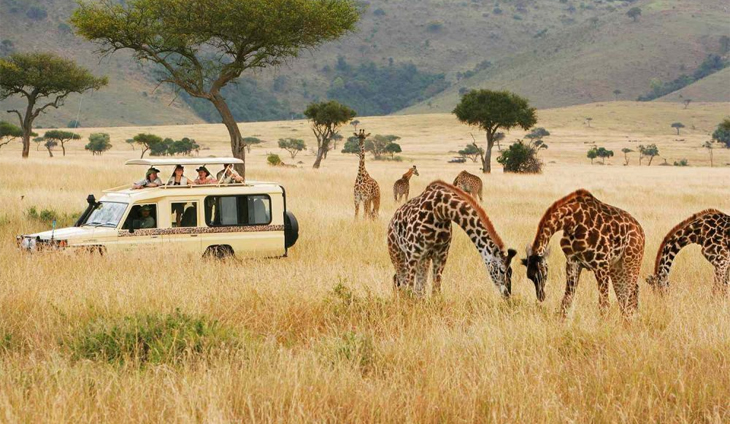

Tensions are mounting. A local activist last week filed suit to block the opening of a new Ritz-Carlton luxury safari lodge with plunge pools and butler service in Kenya’s Maasai Mara reserve. The case is the latest flashpoint as Maasai herders say premium tourism is eroding habitats and livelihoods. In Kenya, communities have complained of alleged land grabs by wealthy investors, while in Tanzania protests against the eviction of tens of thousands of Maasai to make way for hunting lodges have turned deadly in clashes with police.