Senior figures linked to Sudan’s Muslim Brotherhood have sharply escalated their rhetoric in recent days, issuing direct threats against civilians, neighboring states, and the United States, as the group faces mounting public backlash over its role in prolonging Sudan’s war and reviving the extremist methods associated with its decades in power.

The latest wave of statements follows warnings by a retired security officer aligned with the Brotherhood, who threatened attacks against six countries in the region. Shortly afterward, prominent Islamist figure Al-Naji Abdullah went further, publicly threatening an attack on the White House, while senior leader Yasser Obeidallah issued death threats against Sudanese civilians who spearheaded the 2019 uprising that ended the rule of Omar al-Bashir.

Analysts say the remarks reflect the movement’s continued dependence on General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan’s army (SAF) and its outright rejection of any civilian-led political process.

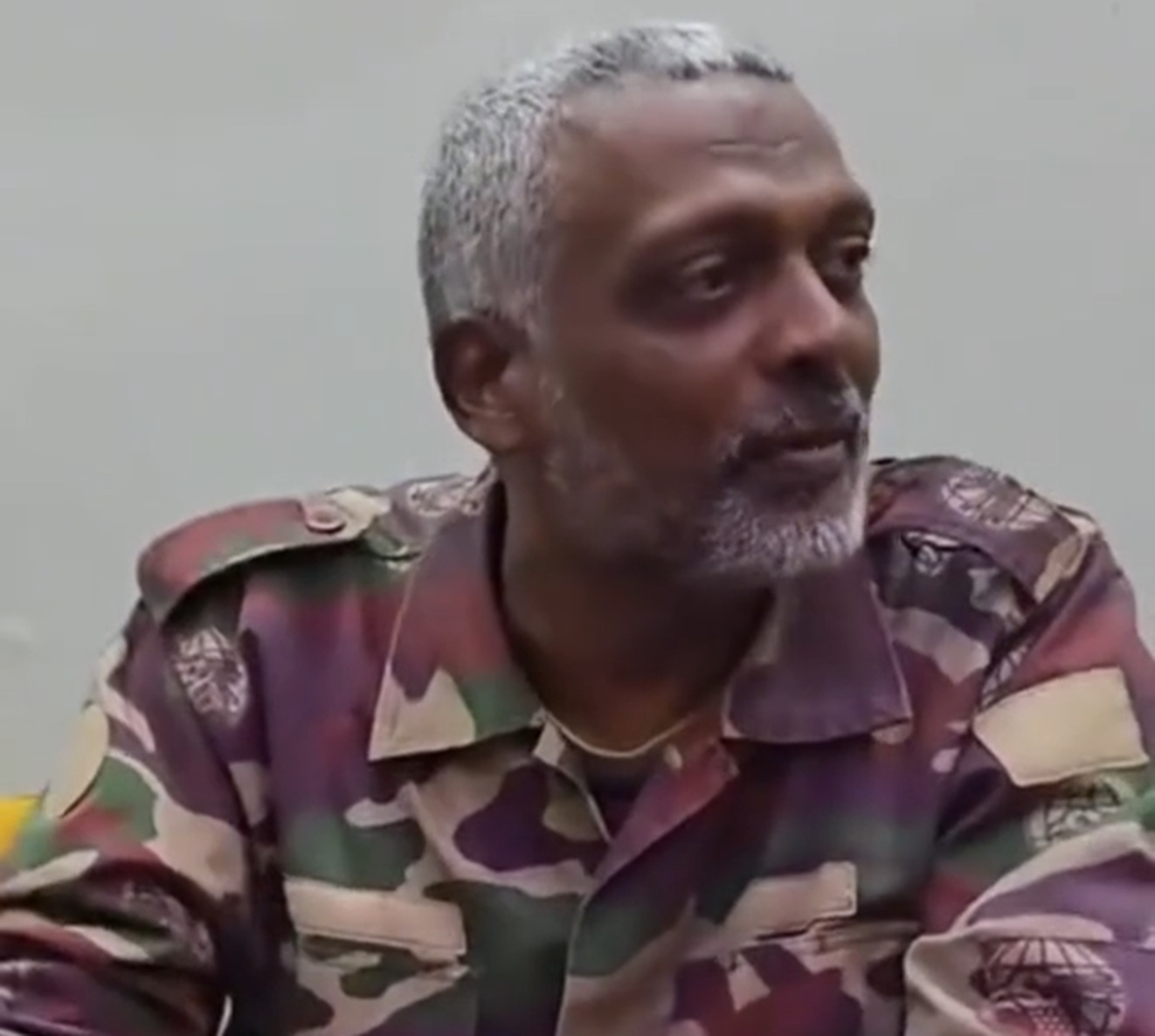

In a video that circulated widely on social media, Al-Naji Abdullah — a former Islamist commander nicknamed the “Emir of Tanks” during the South Sudan conflict of the 1990s — openly called for violence against US targets. “Our wish is to open fire inside the White House,” he said, claiming that the Brotherhood was engaged in a direct confrontation with US President Donald Trump and American intelligence agencies.

In a separate audio recording, former security general Abdel-Hadi Abdel-Basit acknowledged the organization’s past involvement in cross-border targeting operations, asserting that it still possesses the capacity to harm multiple states in the region. He framed the movement’s struggle as one that extends beyond Sudan, describing it as a confrontation with countries enjoying stability and security.

The statements emerged as US lawmakers renewed scrutiny of Sudan’s conflict during congressional discussions, where several speakers argued that the continued influence of Islamist networks within the military establishment lies at the heart of the country’s collapse.

Since the war erupted in April 2023, analysts and rights observers have repeatedly warned of links between Brotherhood-aligned factions supporting the Sudanese army and extremist networks operating beyond Sudan’s borders. Under Islamist rule in the 1990s, Sudan hosted al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, issued passports to foreign militants, and became implicated in major international attacks, including the attempted assassination of Egypt’s former president Hosni Mubarak in Addis Ababa in 1995, the 1998 bombings of US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, and the 2000 attack on the USS Cole.

In another audio message, Yasser Obeidallah accused civilian groups opposing the war and the so-called Quad countries of acting as foreign agents. “Our choice is death,” he declared. “No Quartet or Quintet will open the door for you.”

The rhetoric followed earlier remarks by a tribal leader in eastern Sudan who threatened to open Red Sea ports to Russia as a means of striking the United States, further intensifying concerns over the use of foreign powers as leverage in Sudan’s internal conflict.

At a US congressional hearing last Friday, Ken Isaacs — a former US presidential candidate and former director of the International Organization for Migration — argued that Sudan’s crisis is rooted in decades of Islamist domination. “Since 1989, Islamic extremism has controlled the state,” Isaacs said, blaming the Muslim Brotherhood and its political wing, the National Congress Party, for years of war and terrorism.

He compared the movement’s ideology to that of Hezbollah and al-Qaeda and urged the administration of President Donald Trump and Secretary of State Marco Rubio to intensify efforts to designate the Muslim Brotherhood as a foreign terrorist organization.