Gueva Ba tried to reach Europe by boat 11 times from Morocco, failing each attempt. Then, in 2023, the former welder heard about a new route to the United States by flying to Nicaragua and making the rest of the journey illegally by land to Mexico’s northern border.

“In Senegal, it’s all over the streets — everyone’s talking about Nicaragua, Nicaragua, Nicaragua,” said Ba, who paid about 6 million CFA francs ($10,000) to get to Nicaragua in July with stops in Morocco, Spain and El Salvador. “It’s not something hidden.”

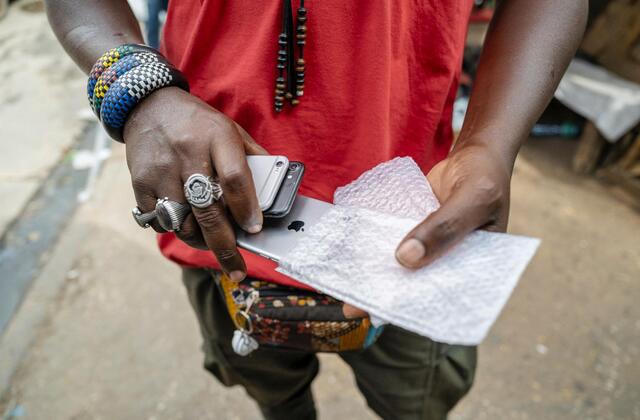

Ba, 40, was deported from the U.S. with 131 compatriots in September after two months in detention, but thousands of other Senegalese have gained a foothold in America. Many turn to savvy travel agents who know the route — touted on social media by those who’ve successfully settled in the U.S.

They are part of a surge in migration to the United States that is extraordinary for its size and scope, with more people from far-flung countries accounting for crossings at the border.

And as with this route used by the Senegalese, more are figuring out plans, making payments, and seeking help via social networks, and apps like WhatsApp and TikTok.

Arrests for illegal crossings on the U.S. border with Mexico reached record highs in December. January saw a drop for the month, but arrests have topped 6.4 million since January 2021. And Mexicans account for only about 1 of 4 arrests, with the others coming from more than 100 countries.

U.S. authorities arrested Senegalese migrants 20,231 times for crossing the border illegally from July to December. That’s a 10-fold increase from 2,049 arrests during the same period of 2022, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Many cross in remote deserts of western Arizona, like Ba, and California.

Word of the Nicaragua route began spreading early last year in Dakar and took hold in May, said Abdoulaye Doucouré, who owns a travel agency that sold about 1,200 tickets from Dakar to Nicaragua in the last three months of 2023, for the equivalent of several thousand dollars each.

“People didn’t know about this route, but with social networks and the first migrants who took this route, the information quickly circulated among migrants,” he said.

Some are motivated by Senegal’s political turmoil — authorities delayed February’s presidential elections by 10 months — but the sudden draw seemed to hinge largely on social media posts and the spread of the route there.

Spikes attributed to social media have occurred in other West African nations, whose people have historically turned first to Europe to flee. Mauritanians have arrived at the U.S. border with Mexico in similarly large numbers, and migrants from Ghana and Gambia have come, too.

Many are eventually released in the U.S. to pursue asylum in immigrant courts that are backlogged for years with more than 3 million cases.

Passports from many African countries carry little weight in the Western Hemisphere, making the journey by land to the United States difficult to even begin. Senegalese can fly visa-free to only two countries in the Americas: Nicaragua and Bolivia, according to The Henley Passport Index.