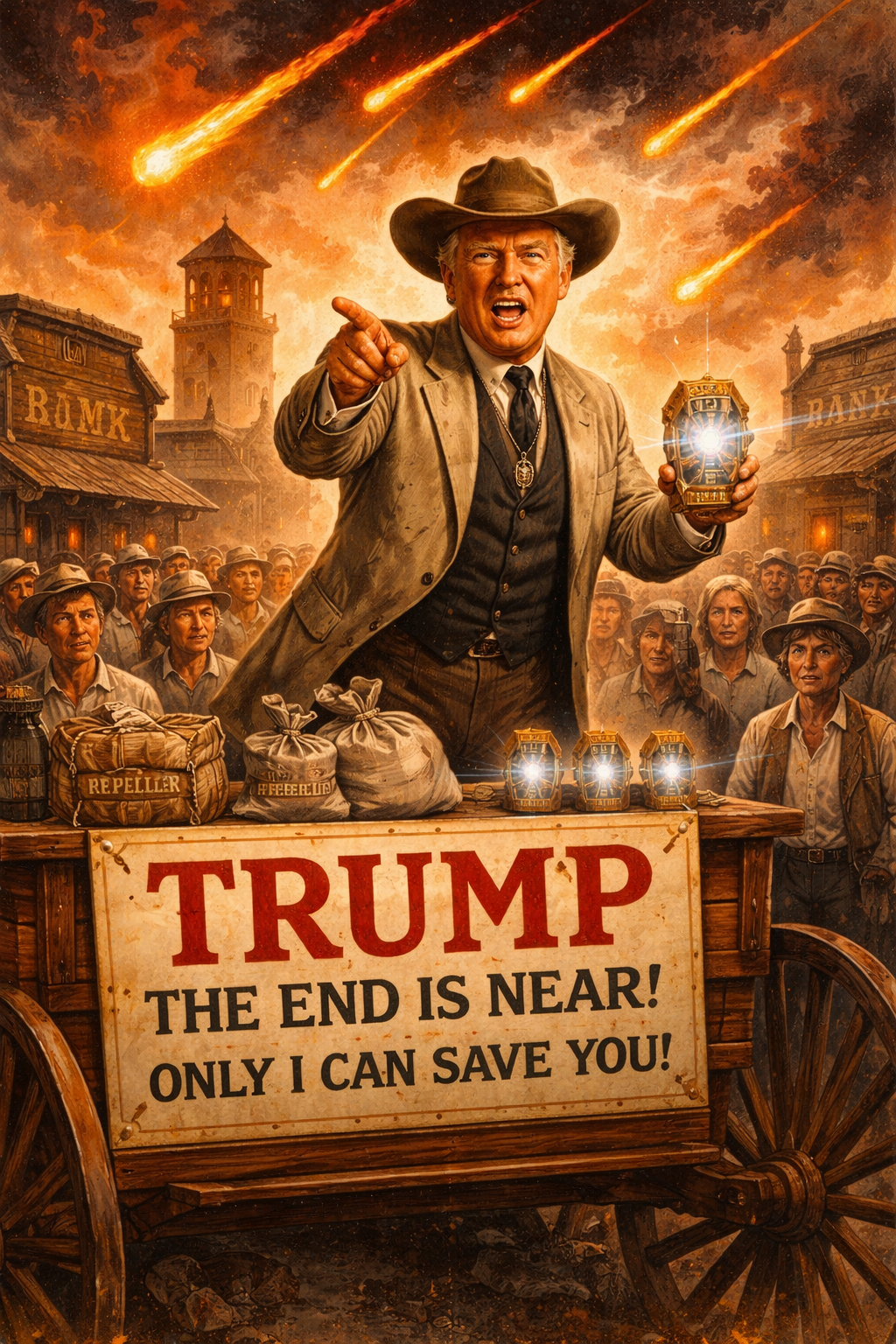

In May 1958, at the height of Cold War anxiety, American television aired an episode of the CBS series Trackdown that now reads like an unsettling study in modern political behavior. Titled “The End of the World,” the episode centers on a traveling conman named Walter Trump who arrives in a small Texas town claiming an apocalyptic disaster is imminent—and that only he can stop it.

Trump’s method is simple: instill fear, claim exclusive knowledge, and offer protection at a price. He warns of a cosmic catastrophe, dismisses skeptics as reckless, invents grandiose scientific credentials, and ultimately sells symbolic “force repellers” while demanding unquestioning loyalty. As doubt grows, so does the cost. The town descends into panic, institutions freeze, and order collapses—not because the threat is real, but because belief spreads faster than truth.

The episode’s Trump does not seize power through force. He does it by narrative. He defines reality, sets the deadline, and frames disbelief as existential risk. Law enforcement hesitates, the courts hide behind procedure, and the crowd chooses reassurance over evidence. By the time the truth emerges, the damage is already done.

More than six decades later, the parallels are difficult to ignore.

In international politics, Donald Trump’s approach has repeatedly followed similar patterns: create a crisis narrative, present himself as the sole actor capable of resolving it, and pressure allies and adversaries alike through uncertainty. From trade wars to NATO, from Iran to China, Trump has often framed global relationships as zero-sum confrontations, warning of catastrophe unless his terms are accepted.

During his presidency, long-standing alliances were treated as transactional protection schemes. NATO members were told security guarantees were conditional. Trade partners were threatened with economic punishment unless they complied. Iran was warned of “fire and fury,” only to be followed by cycles of escalation and sudden de-escalation that left allies unsure of U.S. intentions. In each case, unpredictability itself became leverage.

Like the fictional Trump of Trackdown, the modern version frequently positioned institutions as obstacles rather than safeguards. Multilateral agreements were abandoned. International law was treated as optional. Diplomacy was personalized and theatrical, often conducted via public ultimatums rather than structured negotiation.

The Trackdown episode ultimately makes clear that the conman is not the only problem. The real danger lies in institutional paralysis and collective fear. The sheriff who refuses to act, the judge who insists nothing can be done, and the crowd that silences dissent all enable the fraud. The lie survives not because it is convincing, but because challenging it feels too risky.

In the episode’s closing moments, the apocalypse never arrives. Midnight passes. The town still stands. But the lesson is sharp: fear can empty a bank, break social order, and enrich a liar long before reality intervenes.

That warning, written in 1958, remains relevant today, not as prophecy, but as pattern. The threat is not one man named Trump, fictional or real. It is the political economy of fear, the monetization of panic, and the willingness of institutions to stand aside while narratives do the damage.